Intelligence is a term that is often used to define people, David is “clever” or “bright” maybe even “smart” but it can also be a way in which you define yourself. The problem is that accepting this identity can have a very limiting effect on motivation, for example if someone believes they are not very clever, how hard will they try, effort would be futile. And yet it is that very effort that can make all the difference. See brain plasticity.

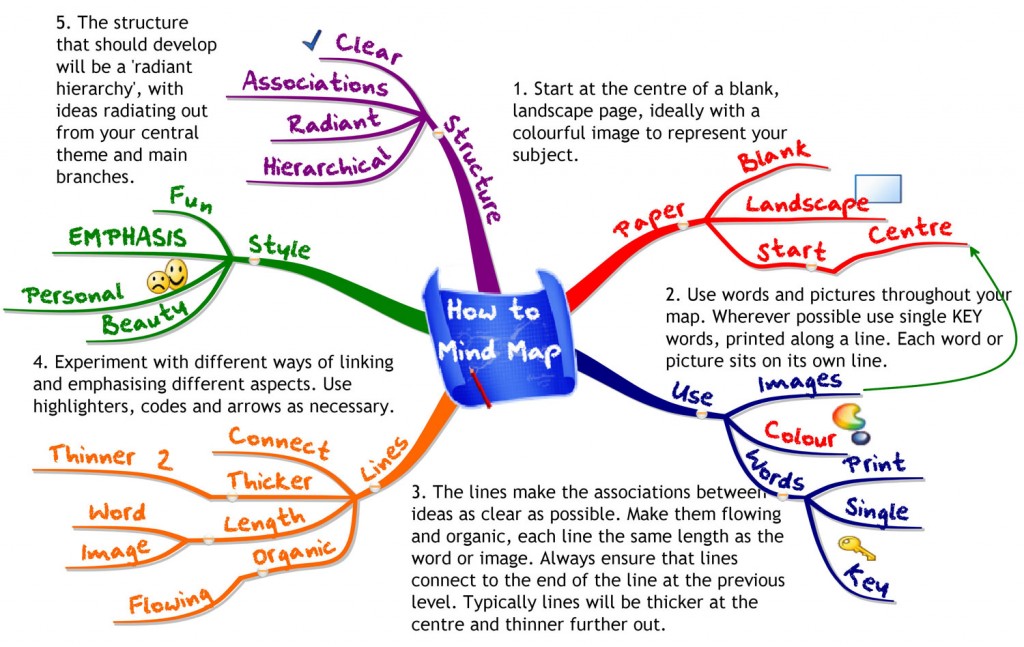

I wrote about an inspiring learning leader back in April this year following the death of Tony Buzan, the creator of mind maps. I want to continue the theme with Howard Gardner (Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education) who I would guess many have never heard of but for me is an inspirational educator.

Multiple Intelligence Theory (MIT)

Now in fairness Howard Gardner is himself not especially inspiring but his idea is. Gardner is famous for his theory that the traditional notion of intelligence, based on I.Q. is far too limited. Instead, he argues that there are in fact eight different intelligences. He first presented the theory in 1983, in the book Frames of Mind – The Theory of Multiple Intelligences.

This might also be a good point to clarify exactly how Gardner defines intelligence.

Intelligence – ‘the capacity to solve problems or to fashion products that are valued in one or more cultural setting’ (Gardner & Hatch, 1989).

- SPATIAL – The ability to conceptualise and manipulate large-scale spatial arrays e.g. airplane pilot, sailor

- BODILY-KINESTHETIC – The ability to use one’s whole body, or parts of the body to solve problems or create products e.g. dancer

- MUSICAL – Sensitivity to rhythm, pitch, meter, tone, melody and timbre. May entail the ability to sing, play musical instruments, and/or compose music e.g. musical conductor

- LINGUISTIC – Sensitivity to the meaning of words, the order among words, and the sound, rhythms, inflections, and meter of words e.g. poet

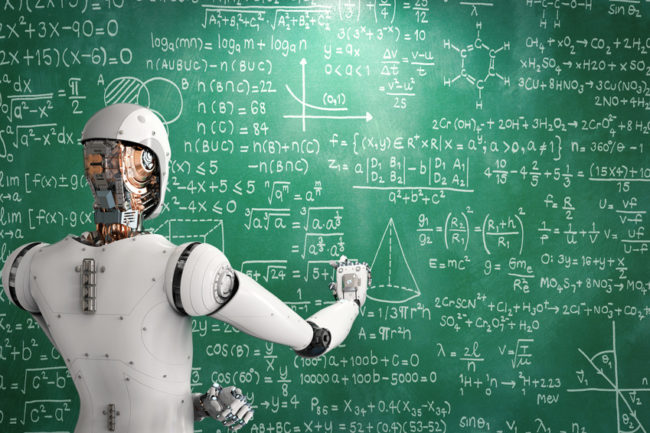

- LOGICAL-MATHEMATICAL – The capacity to conceptualise the logical relations among actions or symbols e.g. mathematicians, scientists

- INTERPERSONAL – The ability to interact effectively with others. Sensitivity to others’ moods, feelings, temperaments and motivations e.g. negotiator

- INTRAPERSONAL- Sensitivity to one’s own feelings, goals, and anxieties, and the capacity to plan and act in light of one’s own traits.

- NATURALISTIC – The ability to make consequential distinctions in the world of nature as, for example, between one plant and another, or one cloud formation and another e.g. taxonomist

I have taken the definitions for the intelligences direct from the MI oasis website.

It’s an interesting exercise to identify which ones you might favour but be careful, these are not learning styles, they are simply cognitive or intellectual strengths. For example, if someone has higher levels of linguistic intelligence, it doesn’t necessarily mean they prefer to learn through lectures alone.

You might also want to take this a stage further by having a go at this simple test. Please note this is for your personal use, its main purpose is to increase your understanding of the intelligences.

Implications – motivation and self-esteem

Gardner used his theory to highlight the fact that schools largely focused their attention on linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligence and rewarded those who excelled in these areas. The implication being that if you were more physically intelligent the school would not consider you naturally gifted, not “clever” as they might if you were good at maths. The advice might be that you should consider a more manual job. I wonder how that works where someone with high levels of physical and spacial intelligence may well find themselves playing for Manchester United earning over £100,000 a week!

But for students this theory can really help build self-esteem and motivate when a subject or topic is proving hard to grasp. No longer do you have to say “I don’t understand this, I am just not clever enough”. Change the words to “I don’t understand this yet, I find some of these mathematical questions challenging, after all, its not my strongest intelligence”. “I know I have to work harder in this area but when we get to the written aspects of the subject it will become easier”.

This for me this is what make Gardner’s MIT so powerful it’s not a question of how intelligent you are but which intelligence(s) you work best in.

“Discover your difference, the asynchrony with which you have been blessed or cursed and make the most of it.” Howard Gardner

As mentioned earlier Howard Gardner is not the most inspirational figure and here is an interview to prove it, but his theory can help you better understand yourself and others, and that might just change your perception of who you are and what you’re capable of – now that’s inspiring!

MI Oasis – The Official Authoritative Site of Multiple Intelligences

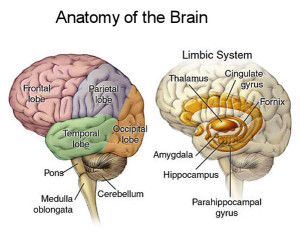

The brain is truly astonishing, if you disagree with that statement it’s just possible you have never heard of circadian rhythms.

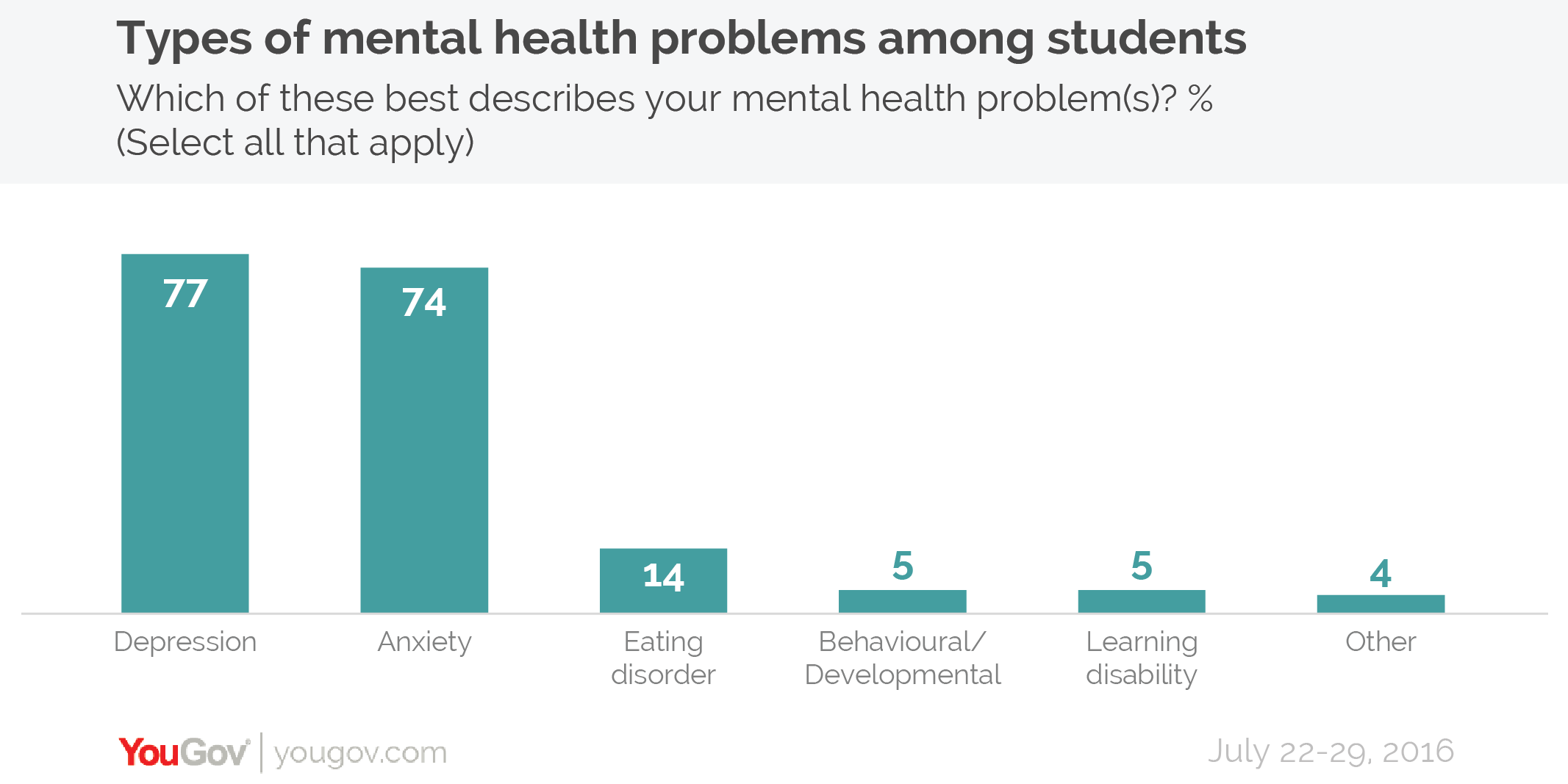

The brain is truly astonishing, if you disagree with that statement it’s just possible you have never heard of circadian rhythms. There is a far more sinister side to the disruption in your circadian rhythm, ongoing research has identified a direct link with mental health disorders such as depression. This is of particular interest given the rise in reported levels of depression amongst students. One area that is being investigated is screen time be that mobile phones or computers. The artificial blue light emitted from these devices could well be confusing your circadian clock.

There is a far more sinister side to the disruption in your circadian rhythm, ongoing research has identified a direct link with mental health disorders such as depression. This is of particular interest given the rise in reported levels of depression amongst students. One area that is being investigated is screen time be that mobile phones or computers. The artificial blue light emitted from these devices could well be confusing your circadian clock.

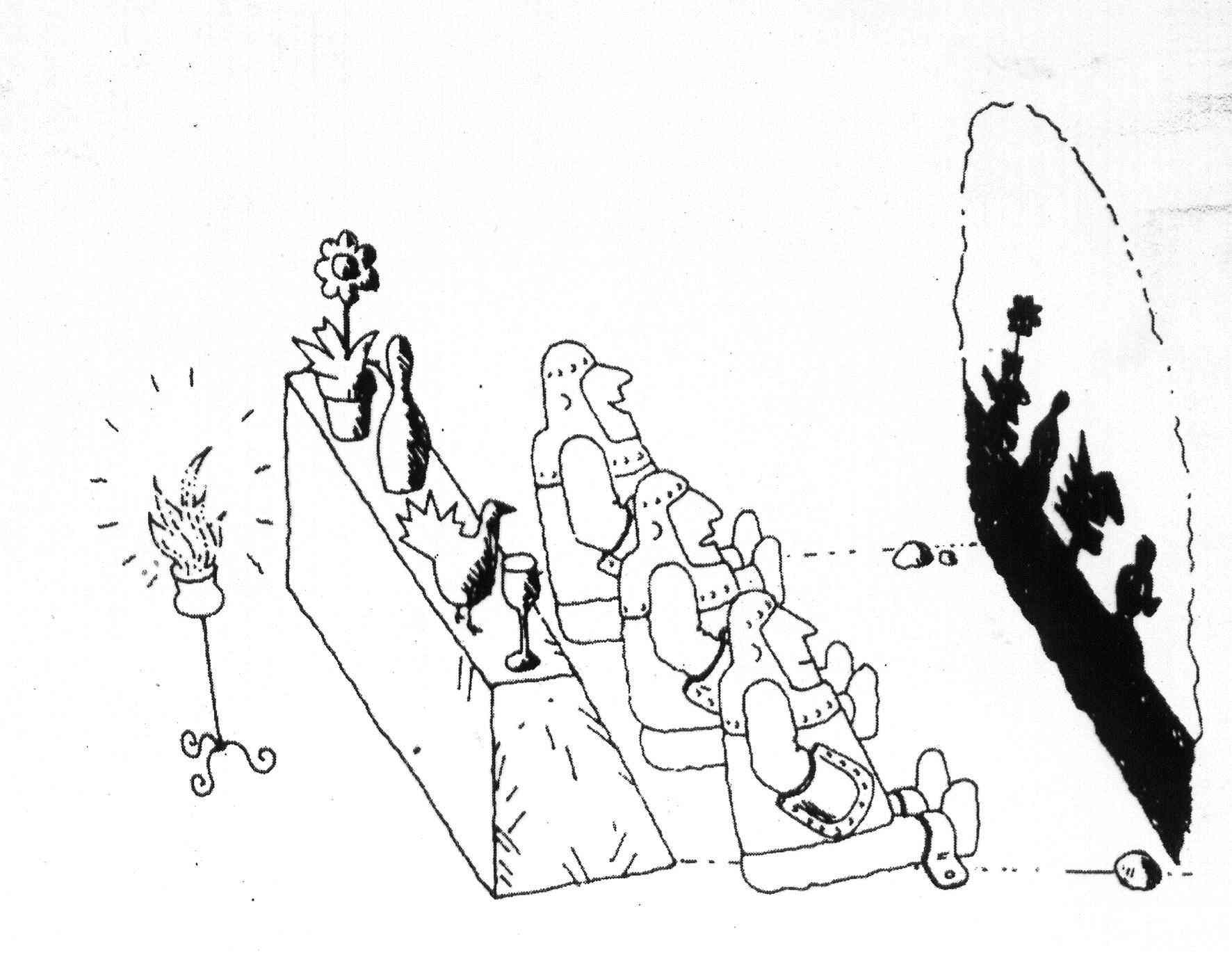

Although Plato is the author, it is Socrates who is the narrator talking to Plato’s elder brother Glaucon.

Although Plato is the author, it is Socrates who is the narrator talking to Plato’s elder brother Glaucon. Richard Feynman who featured in

Richard Feynman who featured in

There are a number of terms that crop up continually in learning, motivation, attention, inspiration,

There are a number of terms that crop up continually in learning, motivation, attention, inspiration,

Welcome to part two, exploring the facts and what really works in learning.

Welcome to part two, exploring the facts and what really works in learning.

A major new idea was presented to the world in 1991, to many it will mean very little but in terms of improving our understanding of the brain it was a milestone.

A major new idea was presented to the world in 1991, to many it will mean very little but in terms of improving our understanding of the brain it was a milestone.