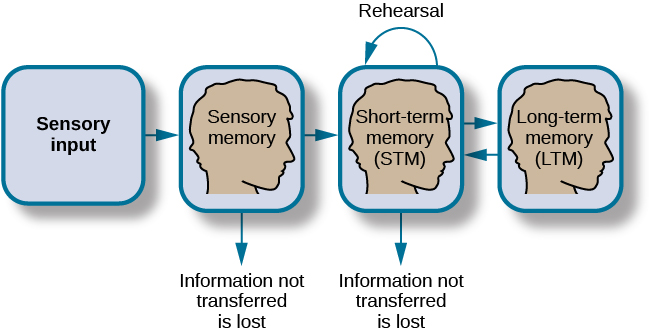

Back in 2017 Dylan Williams, Professor of Educational Assessment at UCL described cognitive load theory (CLT) as ‘the single most important thing for teachers to know’. His reasoning was simple, if learning is an alteration in long term memory (OFSTED’s definition) then it is essential for teachers to know the best ways of helping students achieve this. At this stage you might find it helpful to revisit my previous blog, Never forget, improving memory, which explains more about the relationship between long and short-term memory but to help reduce your cognitive load…. I have provided a short summary below.

But here is the point, if CLT is so important for teachers it must also be of benefit to students.

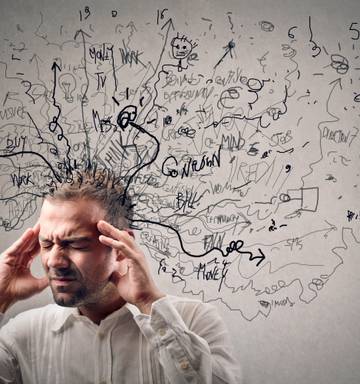

Cognitive load theory

The term cognitive load was coined by John Sweller in a paper published in the journal of Cognitive Science in 1988. Cognitive load is the amount of information that working/short term memory can process at any one time, and that when the load becomes too great, processing information slows down and so does learning. The implication is that because we can’t do anything about the short-term nature of short-term memory, we can only retain 4 + or – 2 chunks of information before it’s lost, learning should be designed or studying methods changed accordingly. The purpose of which is to reduce the ‘load’ so that it can more easily pass into long term memory where the storage capacity is infinite.

CLT can be broken down into three categories:

Intrinsic cognitive load – this relates to the inherent difficulty of the material or complexity of the task. Some content will always have a high level of difficulty, for example, solving a complex equation is more difficult than adding two numbers together. However, the cognitive load arising from a complex task can be reduced by breaking it down into smaller and simpler steps. There is also evidence to show that prior knowledge makes the processing of complex tasks easier. In fact, it is one of the main differences between an expert and a novice, the expert requires less short-term memory capacity because they already have knowledge stored in long term memory that they can draw upon. The new knowledge is simply adding to what they already know. Bottom line – some stuff is just harder.

Extraneous cognitive load – this is the unnecessary mental effort required to process information for the task in hand, in effect the learning has been made overly difficult or confusing. For example, if you needed to learn about a square, it would be far easier to draw a picture and point to it, than use words to describe it. A more common example of extraneous load is when a presenter puts too much information on a PowerPoint slide, most of which adds little to what needs to be learned. Bottom line – don’t make learning harder by including unimportant stuff.

Germane cognitive load – increasing the load is not always bad, for example if you ask someone to think of a house, that will increase the load but when they have created that ‘schema’ or plan in their mind adding new information becomes easier. Following on with the house example, if you have a picture of a house in your mind, asking questions about what you might find in the kitchen is relatively simple. The argument is that learning can be enhanced when content is arranged or presented in a way that helps the learner construct new knowledge. Bottom line – increasing germane load is good because it makes learning new stuff easier.

In summary, both student and teacher should reduce intrinsic and extraneous load but increase germane.

Implications for learning

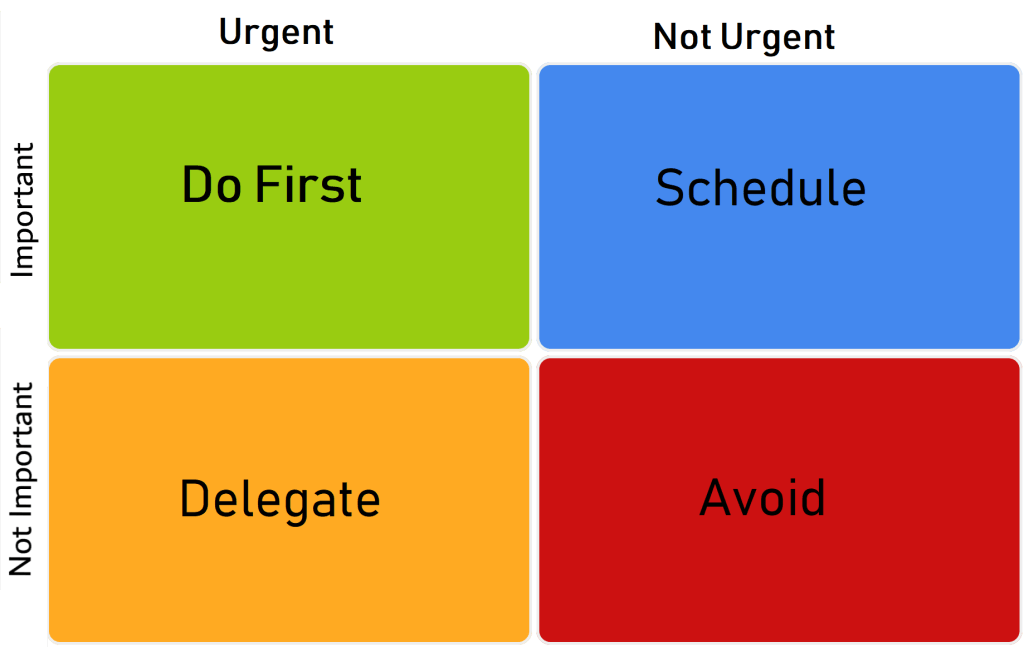

The three categories of cognitive load shown above provide some insight as to what you should and shouldn’t do if you want to learn more effectively. For example, break complex tasks down into simpler ones, focus on what’s important and avoid unnecessary information and use schemas (models) where possible to help deal with complexity. There are however a few specifics that relate to the categories worthy of mention.

The worked example effect – If you are trying to understand something and continual reading of the text is having little impact, it’s possible your short-term memory has reached capacity. Finding an example of what you need to understand will help free up some of that memory. For example…….…if I wanted to explain that short term memory is limited I might ask you to memorise these 12 letters, SHNCCMTAVYID. But because this will exceed the 4+ or – 2 rule it will be difficult and hopefully as a result prove the point. In this situation the example is a far more effective way of transferring knowledge than pages of text.

The redundancy effect – This is most commonly found where there is simply too much unnecessary or redundant information. It might be irrelevant or not essential to what you’re trying to learn. In addition, it could be the same information but presented in multiple forms, for example an explanation and diagram on the same page. The secret here is to be relatively ruthless in pursuing what you want to know, look for the answer to your question rather than getting distracted by adjacent information. You may also come across this online where a PowerPoint presentation has far too much content and the presenter simply reads out loud what’s on the slides. In these circumstances, it’s a good idea to turn down the sound and simply read the slides for yourself. People can’t focus when they hear and see the same verbal message during a presentation (Hoffman, 2006).

The split attention effect – This occurs when you have to refer to two different sources of information simultaneously when learning. Often in written texts and blogs as I have done in this one, you will find a reference to something further to read or listen to, ignore it and stick to the task in hand, grasp the principle and only afterwards follow up on the link. Another way of reducing the impact of split attention is to produce notes that reduce the conflict that arises when trying to listen to the teacher and make notes at the same time. You might want to use the Cornel note taking method, click here to find out more.

But is it the single most important thing a student should know?

Well maybe, maybe not but its certainly in the top three. The theory on its own will not make you a better learner but it goes a long way in explaining why you can’t understand something despite spending hours studying, it provides guidance as to what you can do to make learning more effective but most importantly it can change your mindset from – “I’m not clever enough” to, “I just need to reduce the amount of information, and then I’ll get it”.

And believing that is priceless, not only for studying towards your next exam but in helping with all your learning in the years to come.