“There is no life I know, to compare with pure imagination, living there, you’ll be free, if you truly wish to be. If you want to view paradise, simply look around and view it, anything you want to, do it, want to change the world? There’s nothing to it”

These are a few lines from the song “Pure Imagination” performed by Gene wilder in the original 1971 Willy Wonka movie, always a good watch at Christmas. It was remade with Johnny Depp in 2005 and a prequel called Wonka was released this December to much acclaim, staring Timothée Chalamet. The original story tells of a poor boy named Charlie Bucket who wins a golden ticket to tour the magical chocolate factory of the eccentric Willy Wonka. Although the story still has a contemporary feel, its appeal has more to do with the magical world Wonka creates, the morality of greed, and recognising that actions have consequences.

The point however is, to create such a fantastical, spectacular, stupendous chocolate factory, Wonka required a very special quality – Imagination!

Imagination

Imagination is tricky to define, with many linking it to creativity and contrasting it with knowledge, but I like this explanation provided by Chat GPT, checked of course.

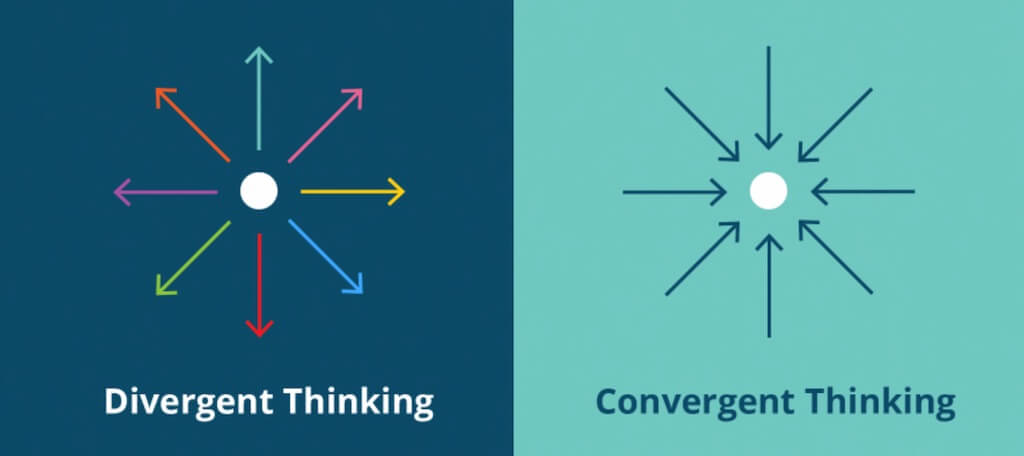

Imagination is the cognitive ability to form mental images, ideas, or concepts that are not directly perceived through the senses. It involves the capacity to create, manipulate, and combine mental representations, allowing individuals to explore possibilities, envision scenarios, and generate novel ideas.

Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Albert Einstein

There is a strong visual element to imagination but it’s not driven by our senses, we are not looking at an object in the real world (external) and creating something new as a consequence. When you use your imagination, its coming from your internal world, often unconsciously influenced by your memories and feelings. In fact, when you imagine something, you don’t have to have experienced it before at all.

Logic will get you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere. Albert Einstein

Imagination, creativity, and knowledge are intricately connected in the process of thinking, especially at the higher levels. Knowledge is the foundation, providing the raw material for imaginative exploration and creative synthesis. Imagination draws upon knowledge, resulting in mental representations and visual possibilities. Creativity transforms these imaginative ideas into valuable outcomes, for example solving a problem or developing a new product.

Creativity is putting your imagination to work, and it’s produced the most extraordinary results in human culture. Ken Robinson

Imagination, original thought and Gen AI

I didn’t think this blog was going to have anything to do with Gen AI, apologies, I was trying to make it Gen AI free. But using it by way of contrast might help with our understanding of imagination and to some extent original thought i.e. ideas, concepts, or perspectives that are unique.

At the time of writing no matter how impressive a Gen AI created poem or picture might be it is not the result of imagination as described above. The AI is simply accessing the huge data sets on which it has been trained and predicting the most likely next word or brush stroke. In other words, it isn’t capable of what we would call “original thought”, that is having new ideas of its own. I should add that when I discussed this point with Chat GPT it disagreed.

The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination.” Albert Einstein

Genetics – And finally in terms of understanding imagination, being imaginative or creative is not thought to be genetic. While genetic predispositions may create a foundation, the development and expression of imagination is shaped more by external influences. (Nichols 1978, Barron & Parisi 1976, Reznikoff 1973).

The neuroscience of imagination – Watch this if your interested as to what is happening in your brain when you use your imagination.

Imagination has given us the steam engine, the telephone, the talking-machine, and the automobile, for these things had to be dreamed of before they became realities. L. Frank Baum

Does imagination help with learning?

All very interesting, at least I hope so but can using your imagination improve learning, of course it can, below are some of the benefits:

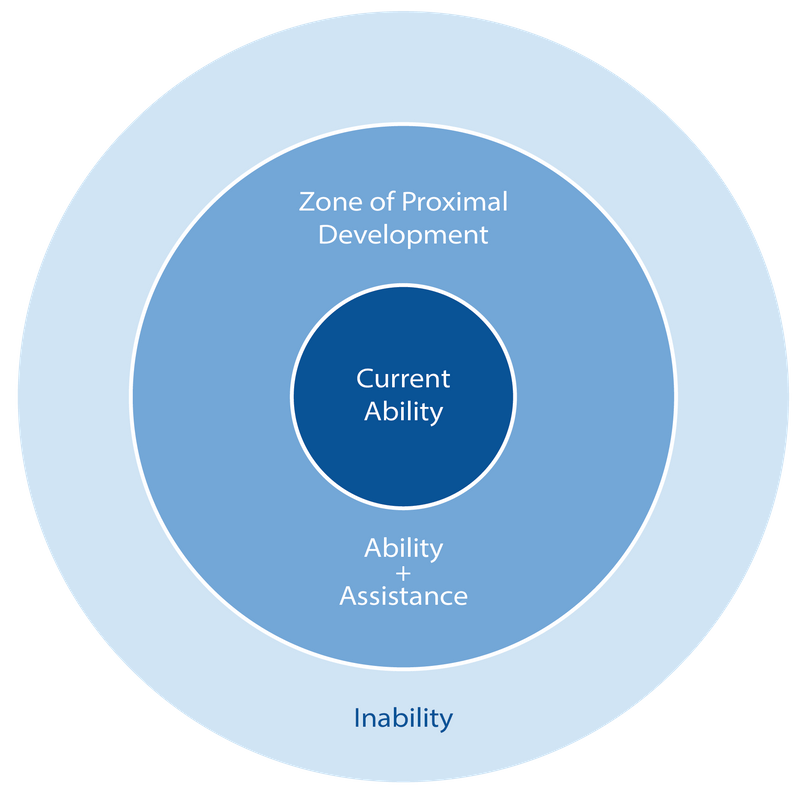

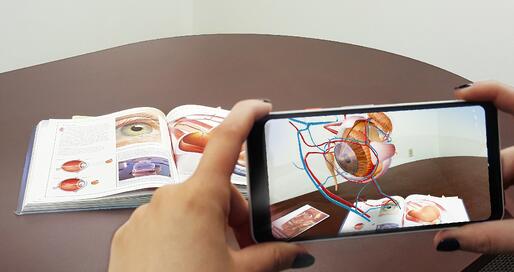

- Brings into play the imagination effect – A study in 2014 required two different groups to learn the parts of the respiratory system. One group were asked to imagine the parts from a text description but without a picture, the other had both text and picture (control). Those who had to imagine the picture did better on a test than the control. The conclusion – people learn more deeply when prompted to form images depicting what the words describe. There are a number of reasons for this, but one is thought to be the reduction in cognitive load.

- Encourages independent learning – The ability to think about a particular problem or situation using your imagination helps develop a more independent approach to learning.

- Increases engagement – Imagination can make learning more engaging and enjoyable partly because the learning becomes more personal, as new information is related to something already known.

- Improved memory retention – Creating mental images or scenarios related to the material being learned can improve memory retention. Imagination often requires visualisation, making it easier to recall information later.

- Facilitates critical thinking – Imagining different scenarios and perspectives encourages critical thinking, allowing the learner to analyse information more deeply and consider various angles, leading to a richer understanding of the subject matter.

- Stimulation of curiosity – Imagination sparks curiosity, motivating learners to explore topics further. This intrinsic type of motivation can then lead to a lifelong learning mindset.

What happened to Charlie Bucket and friends?

Charlie, (Peter Ostrum) only ever stared in Willy Wonka. He later became a Vet in New York. Veruca, Salt (Julie Cole) continued to act but later became a psychotherapist. Violet Beauregarde (Denise Nickerson) also acted for a short while before getting a job as a receptionist. And Michael Bollner (Augustus Gloop) is a lawyer in Germany.

Want to now more – Imagination: It’s Not What You Think. It’s How You Think – Charles Faulkner.

The last word we will give to Willy Wonka……But what do you think it means?

“We are the music makers; we are the dreamers of dreams.” Willy Wonka