This month’s blog is about something especially important to me just now, its an essential component of any real and meaningful relationship – TRUST. Ask yourself how many people do you really trust, three, four probably not that many, a few close friends, and family perhaps. If you trust someone, you believe they are honest and sincere and wont deliberately do anything to harm you, in fact they will always have your best interests at heart. As a consequence, you are more likely to listen carefully to what they say, giving them significant influence over what you think and do.

“Trust takes years to build, seconds to break, and forever to repair.” Amy Rees Anderson

Trust is also one of those intangible qualities that companies and organisations crave, and yet when it matters most, they often fail to keep their end of the bargain. A recent survey by PwC concluded that the trust gap is widening, here are a few other headlines:

- 93% of executives agree that building and maintaining trust improves the bottom line

- It’s getting even harder to build trust – executives are facing more hurdles than before

- 86% of executives say they highly trust their employees, but only 60% of employees feel highly trusted

Who can you trust?

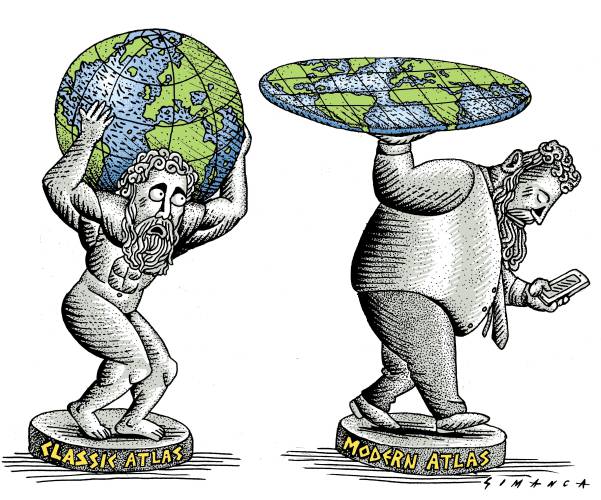

Ipsos the market research company has run a poll on trust in the professions for many years. Their 2023 report identified that the most trusted professions in Britain were: nurses, airline pilots, librarians, doctors, engineers, teachers, and professors. Perhaps not surprisingly the bottom three were politicians, government ministers and advertising executives. Business leaders somewhat disappointingly scored only 30%, just above estate agents! Looking at the list it seems that trust takes a backseat when power and money are part of the equation.

“Trust is the glue of life. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships.” Stephen Covey

Trust in education

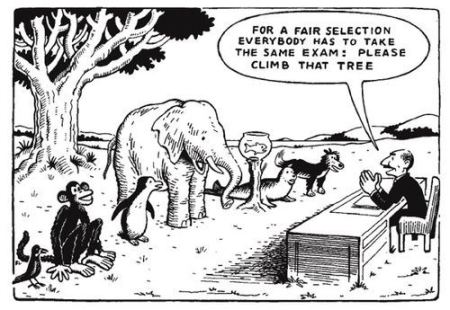

Trust plays a pivotal role in education, influencing various aspects of the learning process. When you think about it students don’t know if what they are being taught is actually worth knowing. They simply trust that the teacher will select relevant content and use the best learning methods to deliver it.

We should probably distinguish trust from respect, authority, and reliance. Respect is where you hold someone in “high regard,” recognising their worth, you might of course trust them as well but its not essential. Authority on the other hand is more about power, a student will “do as they are told” but that doesn’t mean they will see the value in what they are doing. And lastly reliance, this is closer to trust but its still not the same, you can rely on a calculator to come up with the correct answer but you cannot trust it, that’s because there is no relationship.

Think of a situation where the teacher asks the whole class to attempt 10 questions for homework, the problem is that the students don’t see any value in this and think it’s a waste of time. But when they get home, they reflect on what they have been asked to do and complete the questions, not because they have changed their mind but because they believe that the teacher wouldn’t want them to do something that wasn’t in their best interests. The result is that the next time the student is asked to do something, they are more likely to oblige. Okay so this is a rather idealistic view of the teacher, student relationship but hopefully it shows that trust can reach well beyond the walls of a classroom.

What about the neuroscience

Trust is much greater in people with higher levels of oxytocin (OT), which although not classed as a neurotransmitter, (chemicals in the brain that help link neurons) for our purposes we can think of it as being similar. In one experiment individuals administered with OT were more inclined to trust others with their money compared to those given a placebo. If you want to increase levels of OT, but don’t want to give a massage! (physical contact can help), you should demonstrate that you care about the individual and are kind to them. Which when you think about it makes a lot of sense.

“Trust is like the air we breathe – when it’s present, nobody really notices; when it’s absent, everybody notices.” Warren Buffett

Increased engagement and communication

In terms of evidence studies have shown that when students trust their teachers, they are more likely to engage in learning activities, seek feedback, and participate in class discussions (Roorda et al., 2011). This trust enables educators to create supportive learning environments where students feel safe to take risks, ask questions, and explore new ideas. In addition, trust between students and educators facilitates effective communication and collaboration. Research by Bryk and Schneider (2002) suggests that high levels of trust in schools are associated with improved teacher morale and greater job satisfaction.

Conclusions

You can of course be a good teacher without building trust, and a student doesn’t need to trust their teacher to learn but it can be empowering, motivational and in some situation’s life changing. After all, as a teacher what do you have to do, simply have the students’ best interests at heart, and take an interest, and any good teacher will do that. As for the student your role is to trust, which is of course is far more difficult.

To learn more about trust in learning – watch the 4m video – The key role trust plays in learning

My thanks to Monika Platz and her paper on Trust Between Teacher and Student in Academic Education at School which provided inspiration and insight for this blog.

The title of this month’s blog is not mine but taken from what many would consider a classic book about what can realistically be achieved by someone stood at the front of a classroom or lecture theatre, simply talking. Written some 25 years ago but updated recently Donald A. Bligh’s book takes 346 pages to answer the question,

The title of this month’s blog is not mine but taken from what many would consider a classic book about what can realistically be achieved by someone stood at the front of a classroom or lecture theatre, simply talking. Written some 25 years ago but updated recently Donald A. Bligh’s book takes 346 pages to answer the question,

Donald John Trump was born on June 14, 1946, in Queens, New York, the fourth of five children of Frederick C. and Mary MacLeod Trump. Frederick Trump was of German descent, a builder and real estate developer, who left an estimated $250-$300m. His Mother was from the Scottish Isle of Lewis. Trumps early years were spent at Kew-Forest School in Forest Hills, a fee-paying school in Queens. From there aged 13 he went to the New York Military Academy, leaving in 1964. Fordham University was his next stop but for only two years before moving to the Wharton School of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania, from which he graduated in 1968 with a degree in economics. After leaving Wharton Trump went onto to focus full time on the family businesses, he is now said to be worth $3.7bn.

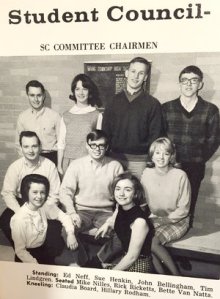

Donald John Trump was born on June 14, 1946, in Queens, New York, the fourth of five children of Frederick C. and Mary MacLeod Trump. Frederick Trump was of German descent, a builder and real estate developer, who left an estimated $250-$300m. His Mother was from the Scottish Isle of Lewis. Trumps early years were spent at Kew-Forest School in Forest Hills, a fee-paying school in Queens. From there aged 13 he went to the New York Military Academy, leaving in 1964. Fordham University was his next stop but for only two years before moving to the Wharton School of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania, from which he graduated in 1968 with a degree in economics. After leaving Wharton Trump went onto to focus full time on the family businesses, he is now said to be worth $3.7bn. Hillary Rodham Clinton was born October 26, 1947, Chicago, Illinois. She was the eldest child of Hugh and Dorothy Rodham. Her father, a loyal Republican, owned a textile business which provided a “comfortable income”. Hillary’s mother who met Hugh Rodham whilst working as a company clerk/typist did not have a college education unlike her father. However Dorothy Rodham is said to have had a significant impact on Hillary and believed that gender should not be a barrier.

Hillary Rodham Clinton was born October 26, 1947, Chicago, Illinois. She was the eldest child of Hugh and Dorothy Rodham. Her father, a loyal Republican, owned a textile business which provided a “comfortable income”. Hillary’s mother who met Hugh Rodham whilst working as a company clerk/typist did not have a college education unlike her father. However Dorothy Rodham is said to have had a significant impact on Hillary and believed that gender should not be a barrier. Clinton, they married in 1975. She graduated with a JD in Law and had a paper published in the Harvard review, under the title “Children Under the Law”.

Clinton, they married in 1975. She graduated with a JD in Law and had a paper published in the Harvard review, under the title “Children Under the Law”. This month’s blog is coming from Malaysia, I have been presenting at the ICAEW learning conference in KL. The only relevance of this, is that as with any lecture/presentation or lesson you have to put yourself in the shoes of your audience and ask, what do they want to get out of this, why are they giving up their valuable time and in many instances money to listen to what you have to say?

This month’s blog is coming from Malaysia, I have been presenting at the ICAEW learning conference in KL. The only relevance of this, is that as with any lecture/presentation or lesson you have to put yourself in the shoes of your audience and ask, what do they want to get out of this, why are they giving up their valuable time and in many instances money to listen to what you have to say?