If you are motivated, learning will be easy and even enjoyable, however motivating people to learn is one of the biggest challenges there is in education. And it’s complicated, what motivates one person does not motivate another.

One area that is worth exploring in order to get a better understanding of motivation is called attribution theory. Could it be that what you believe about the causes of your successes and failures play a part (Weiner 1995), If for example you believe that your success was as a result of hard work would you be motivated to work even harder?

“I’m a greater believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it”. Thomas Jefferson

Attribution theory

Attribution theory was developed by Fritz Heider an Austrian psychologist in the late 1950s. It’s a concept about how people explain the causes of an event or behaviour. The individual’s conclusion will have a significant influence on their emotions, attitudes, and future behaviours. It’s important to note that this is how individuals explain causality to themselves, they are perceptions and interpretations rather than concrete objective realities. Working harder may well be the answer, and yes it was unlucky to be ill on the day of the exam, those are the realities, but attribution theory is about perception. It’s how the individual makes sense of such events that sit comfortably with their view of the world.

“I never blame myself when I’m not hitting. I just blame the bat and if it keeps up, I change bats. After all, if I know it isn’t my fault that I’m not hitting, how can I get mad at myself?” Yogi Berra (baseball player)

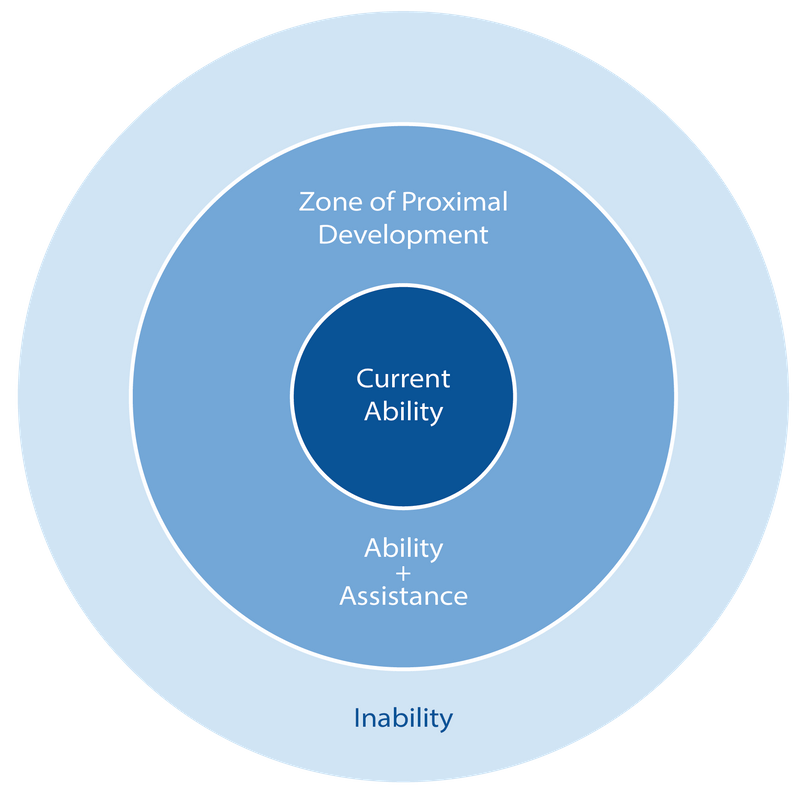

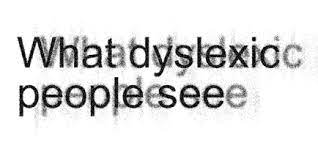

Internal and external – Heider’s basic theory suggested that causes could be internal, something under your control or external, something outside of your control. For example, if you scored highly in an exam, you might conclude that this was because you are very smart and worked hard, these are internal attributions. Conversely, if you did badly in the exam, an external attribution would be that the exam was unfair, and the questions unclear. There is a certain positivity about this perspective, but what if you thought the reason you failed was because you are not bright enough, and the only reason you have been successful in the past was pure luck? The first more positive perspective would build self-esteem, the second erode it.

There is one other aspect of the theory that is worth highlighting, it relates to the perception the individual has in terms of the stability of the attribution. If its stable then it’s thought difficult to change, unstable, easier to change. For example, if you believe that you passed the exam because of your innate intelligence, which is stable, you are more likely to stay the course and overcome setbacks and failures. But if you believe that your intelligence is not fixed, and can get worse, maybe with age, then when faced with a challenge, you may well give up.

“In short, Luck’s always to blame”. Jean de La Fontaine (French Poet)

Why does this matter?

Attribution theory explains how “your perception” of events such as exam success and failure can impact your behaviour and levels of motivation. If you are aware of it you will develop a greater sense of self-awareness and an ability to be able to frame these events in a more positive and helpful way. Remember all that your doing is changing your perception of the event, not the event itself.

Below are a few more observations:

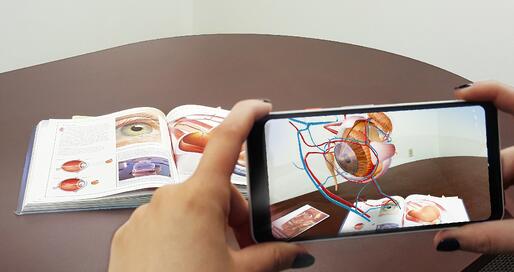

Embrace an attribution style that fosters a growth mindset. Attribute your successes to effort and strategies, and your failures to factors you can change. This mindset promotes a belief that you can develop your abilities over time through hard work.

Use attribution theory to fuel your motivation. When you attribute success to your efforts, it encourages you to work harder in your studies. Likewise, attributing failure to controllable factors can motivate you to adjust your strategies and try again. In order to help maintain your self-esteem and resilience, recognising that sometimes, external circumstances play a role, and it’s not always about your abilities or efforts.

When receiving feedback on your academic performance, ask for specific information about what contributed to your success or failure. This can help you make more accurate attributions and guide your future actions.

This blog is not really about attribution theory, its purpose it to provide you with an understanding of yourself so that you are better prepared for the challenges you will face both inside and outside the exam room.

Attribution or truth…..

“I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life and that is why I succeed”. Michael Jordan

Arnold Schwarzenegger new book– Arni has just brought out a new book called “Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life” and two of his seven tools are “Overcome Your Limitations.” and “Learn from Failure.” Both of which would require some aspect of changes in attribution.