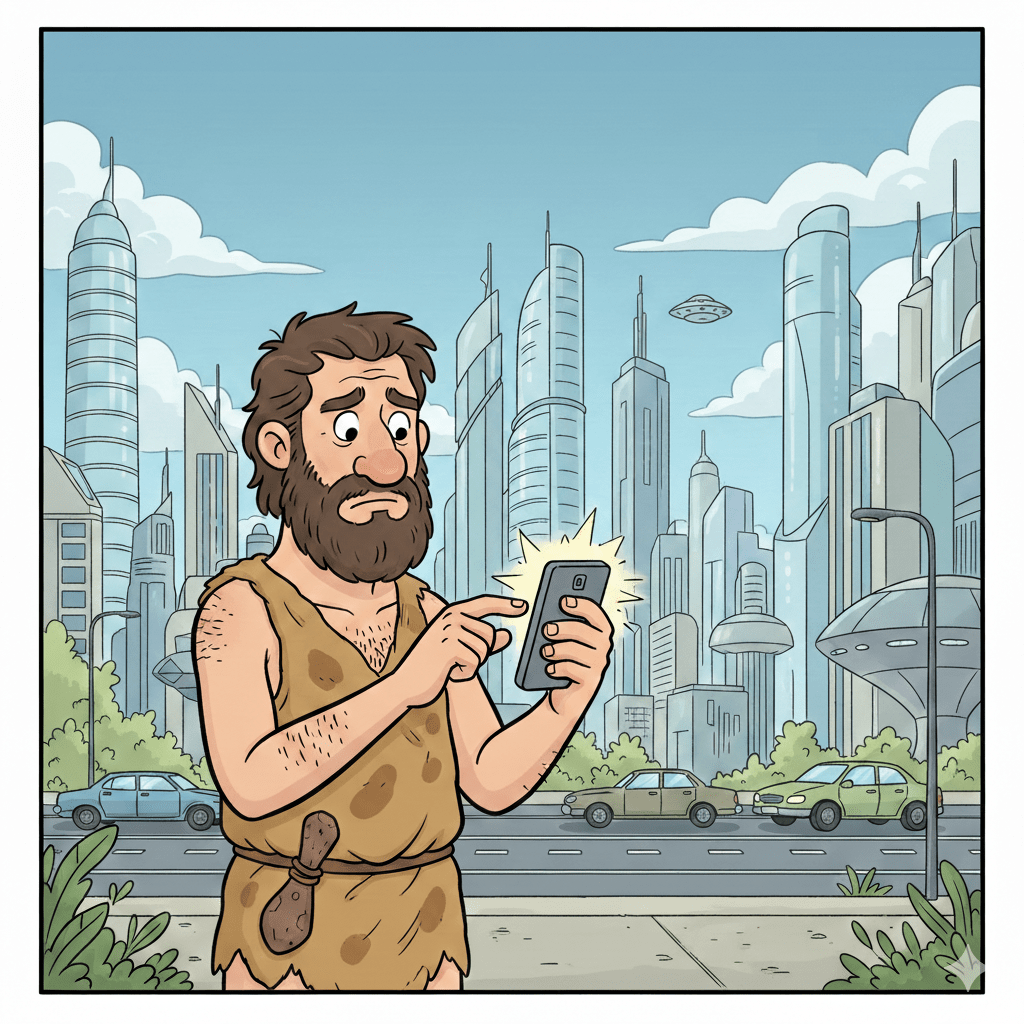

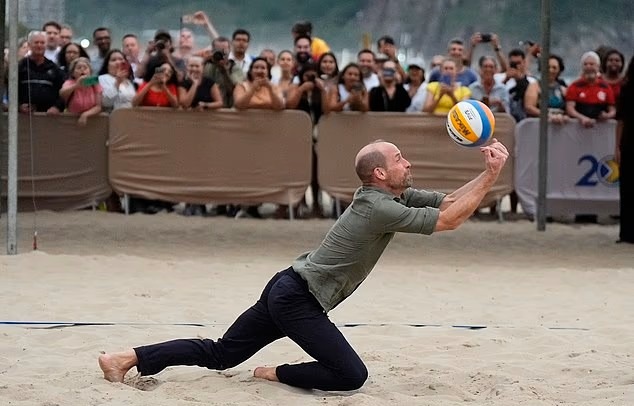

I have long been intrigued by the implications of this headline, returning to it whenever I’m reminded of how technology has reshaped the world and yet how little we, as humans, have evolved to keep pace with it.

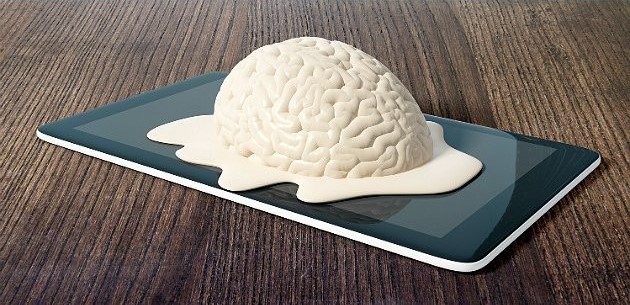

Homo Sapiens are generally understood to be about 300,000 years old, however many of the most transformative changes have been compressed into the last 100 to 200 years. Which in evolutionary terms, is a mere blink of an eye. The brain does evolve of course, but it would take around 10,000 to 30,000 years before there was any noticeable difference.

We live in an incredibly sophisticated world where cars no longer need drivers, it’s possible to translate different languages in real time and we can actually change the DNA inside living cells. But our operating system, “our brain” remains much as it was thousands of years ago.

TL;DR – the short audio version

David Rock’s SCARF Model

Back in 2008 a neuroscientist, author and leadership expert called David Rock recognised this evolutionary mismatch and that our social interactions and decisions were still governed by a primal, binary choice – is this a threat, or is this a reward?

In his paper “SCARF: A Brain‑Based Model for Collaborating with and Influencing Others,” he identified five domains that the brain treats as either threats to be defended against or rewards to be pursued.

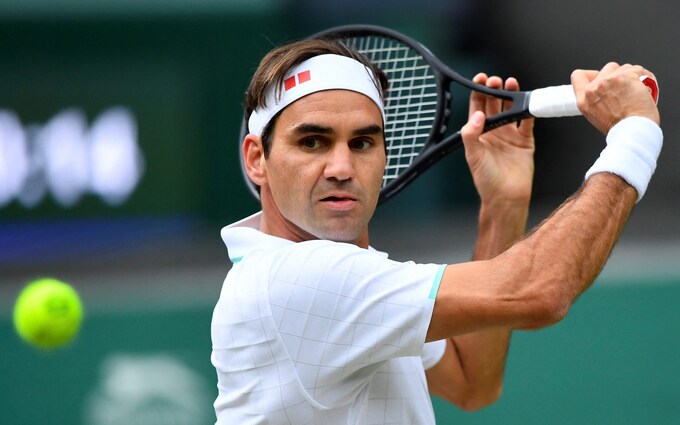

- Status – our sense of where we stand relative to others e.g. A league table that shows you at the top (Reward) or the bottom (Threat)

- Certainty – our ability to predict what happens next e.g. A surprise test (Threat) or a planned one for next week (Reward)

- Autonomy – our feeling of control over our own lives e.g. You must answer this question tonight (Threat) or you can answer any one from three questions tonight (Reward)

- Relatedness – our sense of belonging and connection to others e.g. Asked to study with a group you don’t know (Threat) or studying with a group you do know (Reward)

- Fairness – our perception of whether we are being treated equitably e.g. Being given a poor mark with no explanation (Threat) or receiving a poor mark with a full explanation (Reward)

When you read the comments above, you might think that having the test a week later doesn’t exactly feel like a reward. That’s because the SCARF method considers something a reward if it changes it from being highly uncertain and high‑pressured too certain, more predictable, and less immediate. The key point is, rewards don’t automatically feel good, they simply reduce the threat.

“Good and evil, reward and punishment, are the only motives to a rational creature” – John Locke

What’s also interesting is that brain cannot distinguish between a threat to physical survival and a threat to social status, it responds to both with the same urgency, flood of cortisol, and narrowing of focus. This is exactly what happens when you feel anxious or stressed, which is what can happen in the exam room. In that moment, the brain shifts from learning mode to survival. The amygdala signals danger, stress hormones are released, and attention tightens. The prefrontal cortex responsible for reasoning and working memory, becomes less efficient and emotion takes priority over thought. Neuroscientists sometimes call this an “amygdala hijack.”

Rock concluded – The brain reacts far more strongly to threat than to reward, which means we should reduce the threat wherever possible. Only then can we create the conditions where reward might be felt.

Move people “Away” from threats and “Towards” rewards – David Rock

Implications for learning and study

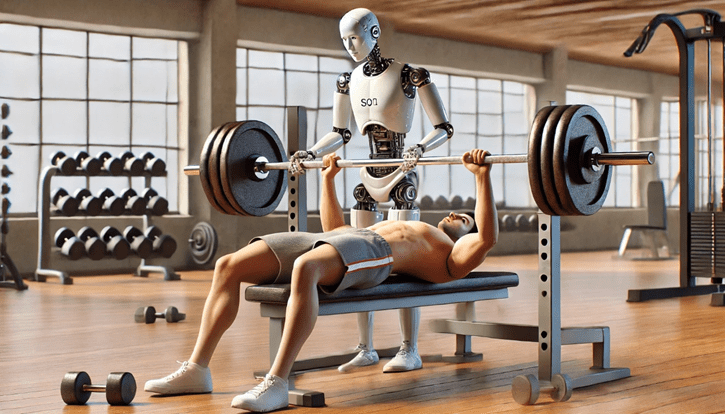

Learning, requires the brain to be in a reward state. When we feel curious, safe, and engaged, the area of our brain responsible for higher-order thinking and problem solving is working well. The moment the brain perceives a threat, everything changes and we are less able to think and learn. Check out this video for more information.

Practical ideas – But how can this help in practice? Understanding the theory is useful, but its real value lies in what we do differently as a result. If the brain is constantly scanning for threat, then small design choices in how we study or teach can either calm that system down or accidentally trigger it.

1. Status – The brain needs to feel capable and respected, not “stupid” or inferior.

Small wins: Start your study session with a 5-minute task you are already good at. This triggers a dopamine release and reinforces a high-status “I can do this” mindset.

Avoid comparison: If looking at high-achieving friends’ social media or grades makes you feel inferior, block notifications during study hours, and stop comparing.

2. Certainty – The brain hates gaps in information and will fill them with anxiety.

Exam paper review: Look at the physical layout of past exam papers. Know exactly how many sections there are, and what type of question’s are asked. Familiarity kills the threat response.

Set micro goals: Instead of saying “I’m studying law tonight,” say “I am covering pages 10-12 and writing three bullet points on each.” The more specific the plan, the more certain the brain feels.

3. Autonomy – The brain thrives when it feels it has a choice.

Give yourself options: Create choice, “Should I study law first or finance?” Even small choices signal to the brain that you are in control.

Choose where you learn: It might be a cafe, the library, or the floor of your room, owning the space increases your sense of autonomy.

4. Relatedness – The brain (people) needs to feel part of a “tribe” rather than isolated and alone.

Study Buddies: Work with people who you know feel the same about study or maybe even find the same areas difficult. This reduces the “social threat” of failure.

Examiners are human: Remember that a real person (who wants to give you marks!) wrote the test. Thinking of it as a communication between two people can lower the threat level.

5. Fairness – The brain reacts strongly to perceived injustice or “trickery.”

Understand the marking guide: Read the marking criteria. When you understand exactly how marks are awarded, the “fairness” filter is satisfied because you know the “rules of the game.”

Self-Compassion: If you have a bad study day, don’t beat yourself up. Treat yourself with the same fairness you’d offer a friend. Internal “unfairness” (being a mean to yourself) can trigger a massive amygdala hijack.

Conclusion

SCARF reminds us that small changes matter. Predictability, choice, belonging, clarity, and respect are not “nice extras,” they are conditions that allow thinking to happen.

And if you are finding study hard, just remember it’s going to be, after all your using a Stone Age brain.