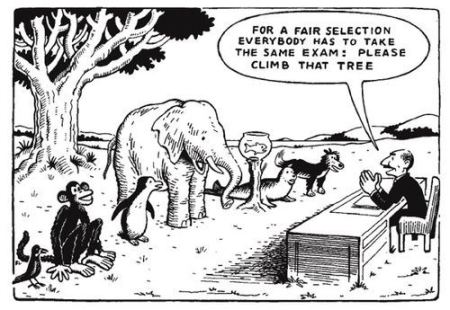

Back in 2014, I wrote two blogs (part 1 & part 2) about examinations and asked if they were fit for purpose. The conclusion – they provide students with a clear objective to work towards, the process is scalable and the resulting qualification is a transferable measure of competency. They are of course far from perfect, exams do not always test what is most needed or valued and when results are presented in league tables, they give a too simplistic measure of success.

However, I didn’t ask if examinations were fair, that is treating students equally without favouritism or discrimination.

In the last two weeks the question around fairness has been in the headlines following the government’s decision to cancel all A level and GCSE examinations in order to reduce the risk of spreading Covid-19. Whilst many agreed with this it did cause a problem, how could we fairly assess student performance without an examination?

Are examinations fair?

This is not a question about the fairness of an exam as a type of assessment, there are for example other ways of testing ability, course work, observations etc. Its asking if the system of which an examination is part treats all students equally, without bias.

In the world of assessment exams are not considered sufficiently well designed if they aren’t both reliable and valid. It might be interesting to use this as a framework to consider the fairness of the exam system.

- Validity – the extent to which it measures what it was designed to measure e.g. add 2+2 to assess mathematical ability.

- Reliability – the extent to which it consistently and accurately measures learning. The test needs to give the same results when repeated. e.g. adding 2+2 is just as reliable as adding 2+3. The better students will get them both right and the weaker students both wrong.

The examining bodies will be very familiar with these requirements and have controls in place to ensure the questions they set are both valid and reliable. But even with sophisticated statistical controls, writing questions and producing an exam of the same standard over time is incredibly difficult. Every year the same questions are asked, have students performed better or is it just grade inflation, were A levels in 1951 easier or harder than today? It’s the reliability of the process that is most questionable.

If we step away from the design of the exam to consider the broader process, there are more problems. Because there are several awarding bodies, AQA, OCR, Edexcel to name but three, students are by definition sitting different examinations. And although this is recognised and partly dealt with by adjusting the grade boundaries, it’s not possible to completely eliminate bias. It would be much better to have one single body setting the same exam for all students.

There is also the question of comparability between subjects, is for example A level maths the same as A level General studies? Research conducted by Durham University in 2006 concluded that a pupil would be likely to get a pass two grades higher in “softer” subjects than harder ones. They added that “from a moral perspective, it is clear this is unfair”. The implication being that students could miss out on university because they have chosen a harder subject.

In summary, exams are not fair, there is bias and we haven’t even mentioned the impact of the school you go to or the increased chances of success the private sector can offer. However, many of these issues have been known for some time and a considerable amount effort goes into trying to resolve them. Examinations also have one other big advantage, they are accepted and to a certain extent the trusted norm and as long as you don’t look too closely, they work or at least appear to. Kylie might be right, “it’s better the devil you know”….. than the devil you don’t.

The mutant algorithm

Boris Johnson is well known for his descriptive language, this time suggesting that the A level problem was the result of a mutant algorithm. But it was left to Gavin Williamson the Secretary of State for Education to make the announcement that the government’s planned method of allocating grades would need to change.

“We now believe it is better to offer young people and parents’ certainty by moving to teacher assessed grades for both A and AS level and GCSE results”

The government has come in for a lot of criticism and even their most ardent supporters can’t claim that this was handled well.

But was it ever going to be possible to replace an exam with something that everyone would think fair?

Clarification on grading

To help answer this question we should start with an understanding of the different methods of assessing performance.

- Predicted Grades (PG) – predicted by the school based on what they believe the individual is likely to achieve in positive circumstances. They are used by universities and colleges as part of the admissions process. There is no detailed official guidance as to how these should be calculated and in general are overestimated. Research from UCL showed that the vast majority, that is 75% of grades were over-predicted.

- Centre Assessed Grades (CAG) – These are the grades which schools and colleges believed students were most likely to achieve, if the exams hadn’t gone ahead. They were the original data source for Ofqual’s algorithm. It was based on a range of evidence including mock exams, non-exam assessment, homework assignments and any other record of student performance over the course of study. In addition, a rank order of all students within each grade for every subject was produced in order to provide a relative measure. These are now also being referred to as Teacher Assessed Grades (TAG)

- Calculated grades (CG) – an important difference is that these are referred to as “calculated” rather than predicted! These are the grades awarded based on Ofqual’s algorithm. They use the CAG’s but adjusts them to ensure they are more in line with prior year performance from that school. It is this that creates one of the main problems with the algorithm…

it effectively locks the performance of an individual student this year into the performance of students from the same school over the previous three years.

Ofqual claimed that if this standardisation had not taken place, we would have seen the percentage of A* grades at A-levels go up from 7.7 % in 2019 to 13.9 % this year. The overall impact was that the algorithm downgraded 39 % of the A-level grades predicted by teachers using their CAG’s. Click here to read more about how the grading works.

Following the outcry by students and teachers Gavin Williamson announced on the 17th of August that the Calculated Grades would no longer be used, instead the Centres Assessed Grades would form the basis for assessing student performance. But was this any fairer, well maybe a little, but it almost certainly resulted in some students getting higher grades than they should whilst others received lower, and that’s not fair.

Better the devil you know

The Government could certainly have improved the way these changes were communicated and having developed a method of allocating grades scenario stress tested their proposal. Changing their mind so quickly at the first sign of criticism suggests they had not done this. It has also left the public and students with a belief that algorithms dont work or at the very least should not to be trusted.

Perhaps the easiest thing to have done would have been to get all the students to sit the exam in September or October. The Universities would then have started in January, effectively everything would move by three months, and no one would have complained about that would they?

Intellectual humility as defined by the authors of a recent paper entitled,

Intellectual humility as defined by the authors of a recent paper entitled,  A point of view is a programme on radio 4 that allows certain well-read, highly educated individuals, usually with large vocabularies to express an opinion. It lasts 10 minutes and is often thought provoking, concluding with a rhetorical question that has no answer.

A point of view is a programme on radio 4 that allows certain well-read, highly educated individuals, usually with large vocabularies to express an opinion. It lasts 10 minutes and is often thought provoking, concluding with a rhetorical question that has no answer.

university entrance exam is a major problem. The government has not been slow to react and for the first time anyone found cheating will face a possible seven year jail sentence. In Ruijin, east China’s Jiangxi Province, invigilators use instruments to scan students’ shoes before they entered the exam hall, while devices to block wireless signals are also used to reduce the opportunity to cheat.

university entrance exam is a major problem. The government has not been slow to react and for the first time anyone found cheating will face a possible seven year jail sentence. In Ruijin, east China’s Jiangxi Province, invigilators use instruments to scan students’ shoes before they entered the exam hall, while devices to block wireless signals are also used to reduce the opportunity to cheat.