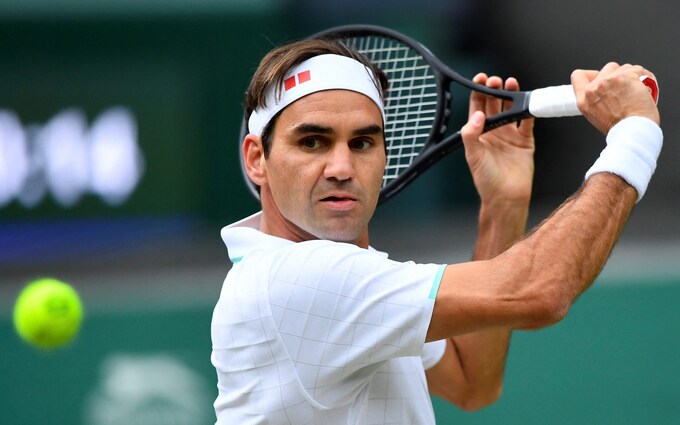

Roger Federer is widely regarded as one of the greatest tennis players of all time and often referred to as a master of tennis. His extraordinary talent, remarkable achievements, consistency, and longevity in the sport have solidified his status as a tennis legend. He also seems to be a very nice bloke!

Relevance to learning?

To improve your position in the tennis rankings, you must first prove yourself at the lower levels before you move to the higher ones, which seems like a pretty solid idea, and yet that’s not how it works in education. If you think back to your school days, although there were different recognised levels of ability within a year, everyone progressed to the next stage of learning based on age. This could mean that you were studying something at a higher level having not mastered the basics at the lower one.

What is Mastery

Mastery learning is an educational approach where learners are expected to achieve a high level of proficiency or mastery in a particular subject or skill before progressing to more advanced material or a higher level. In other words, you must demonstrate mastery of the current material before moving on. For example, in a math’s lesson learners may be required to demonstrate proficiency in solving algebraic equations before moving on to more advanced topics such as calculus. Similarly, in English, learners must demonstrate their proficiency in grammar and punctuation before progressing to writing essays.

Benjamin Bloom, remember him, is often credited with pioneering the concept of mastery learning. In the 1960s. Bloom proposed the idea as a response to the limitations of traditional instructional methods, which often resulted in some learners falling behind while others moved ahead without mastering the material. He emphasised the importance of ensuring that all learners achieve a solid understanding of core concepts before progressing to more advanced topics. This approach required personalised instruction, continuous assessment, and opportunities for remediation to support every learner in reaching mastery. An example of this type of mastery teaching can be found in the personal tutor market, where parents pay an expert to coach and mentor their children so that they will be able to ace high stake tests.

There is also substantial evidence supporting the effectiveness of mastery learning. Several studies have highlighted the advantages, indicating that learners taught using mastery typically exhibit superior academic performance, greater retention of information, and deeper comprehension compared to those instructed using traditional methods. For instance, a meta-analysis published in the “Review of Educational Research” in 1984, analysed 108 studies on mastery learning and concluded that learners consistently outperformed their counterparts on standardised tests and other metrics of academic attainment.

Mastery grade – Although the emphasis in mastery is on ensuring that learners understand and can apply the material, rather than achieving a specific grade, if the assessment method includes questions, then there has to be a “pass mark”. Although the exact percentage may vary, I saw 80% – 85% mentioned, the consensus seems to be 90% or higher.

“Ah, mastery… what a profoundly satisfying feeling when one finally gets on top of a new set of skills… and then sees the light under the new door those skills can open, even as another door is closing.” Gail Sheehy

The impact of technology

While we have seen that the effectiveness of mastery learning has been proven it is not without its challenges. One issue is the increased time needed, the result of personalised tuition, and additional resources e.g. more questions and course materials. This can put a significant strain on any organisation that might result in them cutting corners in practice. However, this is where technology can really help, we are now in the age of AI and adaptive learning which has the potential to offer the high levels of personalisation required to deliver at scale on the mastery promise. Which could mean that mastery and all its benefits becomes well within the reach of everyone rather than a privileged few.

But, but, but the devils in the detail

In practice there are of course other problems, what role if any will teachers play, will there need to be significant retraining? Who will pay for all of this, and what of the social stigma that may result for those held back because they are not “bright enough”?

Three bigger questions:

- Firstly, there is the argument that by focusing on mastering the component parts of a subject, the wider learning is lost, for example the cultivation of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In addition, attaining genuine mastery for all learners within a given timeframe poses challenges where the demographic is more diversified in terms of learning styles, backgrounds, and abilities.

- Secondly, how do we really know if a subject has been learned, let alone mastered. Although someone might have moved to the next topic having scored 92% 3 months earlier, what if the test itself wasn’t sufficiently robust for the level of understanding required at the higher level?

- And lastly, we know that as we progress our tendency to forget increases, unless of course that original information is revisited, think here about the forgetting curve. While the speed at which we forget varies greatly, the consistent observation from decades of research is that, with time, we inevitably lose access to much of the information once retained.

Now there are answers for most of these, however there is the potential for well-meaning organisations to promote so called “mastery courses” when in reality they are fundamentally flawed.

What does this all mean

For learners – Mastery is compelling and should be kept in mind when studying. Going back over something to make sure you understand it will not only reinforce what you already know but builds a solid base from which to move forward. However, there will be times when you don’t fully grasp something and time runs out, leaving you no alternative but to move on. The secret here is not to worry, it might be that this particular piece of knowledge or skill is not required in the future and if it is, you can always go back and learn it, again!

For educators – Mastery is certainly something worth pursuing but be careful, it’s very easy to get caught up in the ideal and create something that looks like it’s working but it’s not because of a lack of attention to the detail required to make this work in practice.

Unfortunately I couldn’t find anything about mastery from Roger Federer, but I’m sure he would wholeheartedly endorse this by a master with a different skill.

“If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all.” Michelangelo