What we need to learn is changing, knowledge is free, if you want the answer just google it. According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Survey, there is an ever-greater need for cognitive abilities such as creativity, logical reasoning and problem solving. And with advances in AI, machine learning and robotics many of the skills previously valued will become redundant.

No need for the Sage on the stage

These demands have led to significant change in the way learning is happening, no longer should students be told what to think, they need to be encouraged to think for themselves, Socratic questioning, group work, experiential learning and problem based learning have all become popular, and Sir Ken Robinson Ted lecture, do schools kill creativity has had 63 million views.

Sir Kens talk is funny and inspiring and I recommend you watch it, but I want to challenge the current direction of travel or at least balance the debate by promoting a type of teaching that has fallen out of fashion and yet ironically could form the foundation upon which creativity could be built – Direct Instruction.

Direct Instruction – the Sage is back

The term direct instruction was first used in 1968, when a young Zig Engelmann a science research associate proved that students could be taught more effectively if the teacher presented information in a prescriptive, structured and sequenced manner. This carefully planned and rigid process can help eliminate misinterpretation and misunderstanding, resulting in faster learning. But most importantly it has been proven to work as evidenced by a 2018 publication which looked at over half a century of analysis and 328 past studies on the effectiveness of Direct Instruction.

Direct Instruction was also evaluated by Project Follow Through, the most extensive educational experiment ever conducted. The conclusion – It produced significantly higher academic achievement for students than any of the other programmes.

The steps in direct instruction

It will come as no surprise that a method of teaching that advocates structure and process can be presented as a series of steps.

Step 1 Set the stage for learning – The purpose of this first session is to engage the student, explaining specifically what they should be able to do and understand as a result of this lesson. Where possible a link to prior knowledge should also be made.

Step 2 Present the material – (I DO) The lesson should be organised, broken down into a step-by-step process, each one building on the other with examples to show exactly how it can be applied. This can be done by lecture, demonstration or both.

Step 3 Guided practice – (WE DO) This is where the tutor demonstrates and the student follows closely, copying in some instances. Asking questions is an important aspect for the student if something doesn’t make sense.

Step 4 Independent practice – (YOU DO) Once students have mastered the content or skill, it is time to provide reinforcement and practice.

The Sage and the Guide

The goal of Direct Instruction is to “do more in less time” which is made possible because the learning is accelerated by clarity and process.

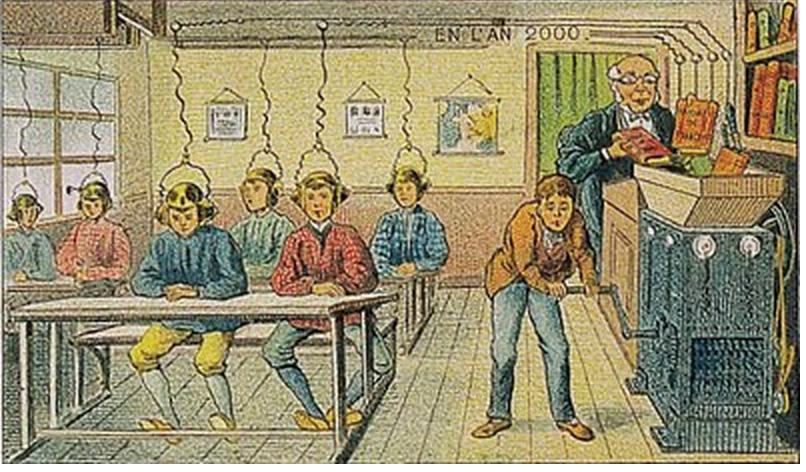

There are of course critics, considering it a type of rote learning that will stifle the creativity of both teacher and student, and result in a workforce best suited for the industrial revolution rather than the fourth one. But for me it’s an important, effective and practical method of teaching. That when combined with inspirational delivery and a creative mindset will help students develop the skills to solve the problems of tomorrow or at least a few of them.

Pingback: I Do, We Do, You Do – The importance of Scaffolding | Pedleysmiths Blog

Pingback: Blooms 1984 – Getting an A instead of a C | Pedleysmiths Blog

Pingback: Synergy – Direct Instruction part 2 | Pedleysmiths Blog

No I haven’t Paul, thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Hi Stuart

Have you read an article by Kirschner, Sweller and Clark from Educational Psychologist 2010 on this subject?

I have long believed that we are at risk of promoting active learning too early in the process when the students don’t yet know what activity is needed…

Cheers

Paul

LikeLike